‘The only rule is there are no rules’ an Interview with artist Jim Anderson

We had the pleasure to meet and chat with artist Jim Anderson, maker of prints, mosaics and hand-made paper. His ecological and environmentally friendly approach is something that we at Lawrence value very highly. Read on for our interview with Jim and get inspired by his beautifully colourful art.

How did you get into printmaking?

I dabbled in printmaking - using the silkscreen - as an A level pupil at school; but I started in earnest in 1883-84 during my Foundation Course year at Cambridge College of Arts and Technology. The print studio was in the draughty church hall of St. Barnabas’ church, and the printmaking tutor was a cantankerous but inspirational man named Walter Hoyle, who had been one of the circle of artists around the designer Edward Bawden. Walter had a fanatical obsession with the materials of printmaking, and a very visceral sense of the alchemy of it all. At the time I was captivated by Dada and Surrealism (still am) and was entranced by the opportunities different print media seemed to offer for lucky accidents.

After Foundation course I took a degree in English and American literature, which gave me the chance to do a lot of theatre design. All the while I carried on making etchings and collagraphs at a printmakers’ co-operative. Working for my degree with words and stories, I grew to like the fact that printmaking seemed much more able than other media, such as painting, to encompass literary and storytelling elements. I liked the fact that print included the traditions of comics and posters and cheap ephemeral art – it wasn’t necessarily ‘high’ art.

We spoke about your piece named ‘Sargasso’, which we chose for our RE Original Print Show prize. You mentioned that it was inspired by the growing numbers of jellyfish in the ocean caused by global warming, is your work usually concerned with the environment?

We had the pleasure to meet and chat with artist Jim Anderson, maker of prints, mosaics and hand-made paper. His ecological and environmentally friendly approach is something that we at Lawrence value very highly. Read on for our interview with Jim and get inspired by his beautifully colourful art.

How did you get into printmaking?

I dabbled in printmaking - using the silkscreen - as an A level pupil at school; but I started in earnest in 1883-84 during my Foundation Course year at Cambridge College of Arts and Technology. The print studio was in the draughty church hall of St. Barnabas’ church, and the printmaking tutor was a cantankerous but inspirational man named Walter Hoyle, who had been one of the circle of artists around the designer Edward Bawden. Walter had a fanatical obsession with the materials of printmaking, and a very visceral sense of the alchemy of it all. At the time I was captivated by Dada and Surrealism (still am) and was entranced by the opportunities different print media seemed to offer for lucky accidents.

After Foundation course I took a degree in English and American literature, which gave me the chance to do a lot of theatre design. All the while I carried on making etchings and collagraphs at a printmakers’ co-operative. Working for my degree with words and stories, I grew to like the fact that printmaking seemed much more able than other media, such as painting, to encompass literary and storytelling elements. I liked the fact that print included the traditions of comics and posters and cheap ephemeral art – it wasn’t necessarily ‘high’ art.

We spoke about your piece named ‘Sargasso’, which we chose for our RE Original Print Show prize. You mentioned that it was inspired by the growing numbers of jellyfish in the ocean caused by global warming, is your work usually concerned with the environment?

Sargasso by Jim Anderson

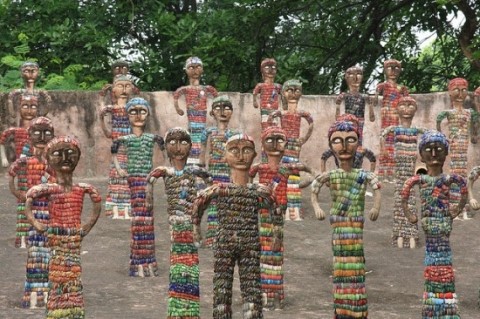

I am very concerned about and interested in ecological matters, but I don’t think it shows explicitly in the imagery of my work, except for a handful of pieces (perhaps including ‘Sargasso’). Without consciously intending to do so, I have arrived at a more or less ecologically-minded way of working. I have always been interested in recycling (my parents were war-time children, so we grew up hearing a lot about rationing and make-do-and-mend). I started making handmade paper in the 80s because it was cheap, and fun (a bit like making mud-pies), and its lumpy unpredictability seemed like a tiny but enjoyably subversive gesture against all things yuppified and mass-produced. I like to make prints which I can transport on the back of my bicycle; where possible I like to bypass complex or wasteful paraphanelia or processes. When I started making mosaics in the late 90s it was chiefly a reaction to reading about all those wonderful ‘outsider’ artists, such as Nek Chand in India, who have created things of wonder out of the stuff society discards. Trash to treasure.

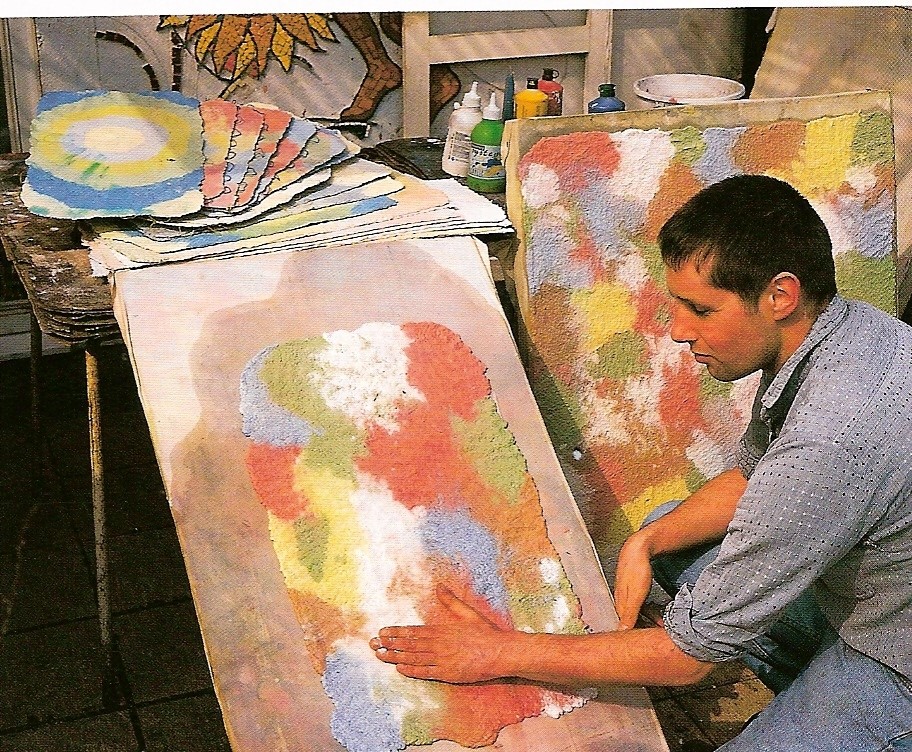

Nek Chand sculptures. Chandigarh, India

In the early 2000s I spent some time in Kenya working on mosaic projects; and found it inspiring that – through necessity – a number of the artists I met there took it for granted that their work would be created from reclaimed materials. As regards art having a ‘message’ – in general I think that art which tries to be didactic ends up looking pretty simple-minded (though ironically a number of my favourite creative people – for example Diego Rivera, Ben Shahn, Bertolt Brecht, or – to bring things a bit more up to date - the contemporary illustrator-cum-provocateur Molly Crabapple – are unashamedly didactic in their intentions). You use recycled materials in your work, and even make your own paper. Can describe the process you go through to create a typical print. I am usually working on several pieces at once, often using a number of different media. Sometime I put a piece aside for several years if I am unsure where it is going. So I’m not sure I have a very typical ‘routine’. But very broadly, a work along the lines of ‘Sargasso’ is created thus; I usually start with a form of collagraph plate – this can be constructed from old hardboard, string, sand, glue, sawdust, hair, and other abandoned materials, stuck together and sealed with carpenters glue…… This collaged plate can then be used to intaglio-print the major elements of the image onto pieces of handmade paper. The paper onto which I print is an important part of the process. I was taught to make handmade paper by a kind South African artist named Susan Rothenberg, whom I met at Oxford Printmakers’ Co-operative in 1984. It was a craft I was eager to learn, because - when one was trying to make something (hopefully) unique - it seemed a little perverse to print onto a piece of flat mass-produced paper. My paper is cooked up from soft rags, scraps of reclaimed paper and card, and occasionally organic matter such as human hair. The ingredients are torn into pieces about the size of a thumbnail, soaked in water for a few days, then mixed with more water and perhaps a little glue or size, before being pulped in a Kenwood blender until the mixture is the consistency of thin porridge. This pulp can be coloured by stirring into it acrylic paints or fabric dyes. I then spread the multi-coloured porridge out onto large pieces of old sheet stretched out on boards, and leave the water to run off and the paper to dry. When dry it can be peeled off. It has the texture and appearance of soft pastel-hued crispbread. I enjoy working onto this unpredictable, spongy, rough-hewn material as I feel it makes the final print into more of an object, more of a thing, as opposed to a flat image impressed onto an even-surfaced industrial product. After the initial collagraph structure of the image has been printed on the handmade paper, I usually work over it and embellish it with a cocktail of lino-cut, stencil, drypoint, and hand-colouring. Because of the variations in the pieces of paper, I can never really achieve an ‘edition’ of identical prints. Your prints are quite lively with strong narratives, what type of literature inspires you the most? All sorts…. The Beano; Edward Lear; Nikolai Gogol; Walt Whitman; Charles Dickens; Bertolt Brecht; Margeret Atwood; H.P. Lovecraft; Newspapers (both ‘quality’ and ‘tabloid’, for their vigorous use of fantasy); William Gibson; Fairy tales and ancient myths. I am presently reading the novels of A.S. Byatt – a bit wordy but full of ideas. I’m not sure there is any particular logic to my reading matter. We understand you make mosaics when you aren’t printmaking? Are the mosaics an extension to your printmaking or do you keep the ideas and thought process separate?

War memorial mosaic

They are all very much intermingled. I usually work on mosaic commissions in the morning, and prints and paintings in the late afternoon and evening. Often an image or idea that I first use in a mosaic will later turn up in a print or a painting; or vice versa. As much as I can, I use recycled or reclaimed materials in my mosaics, so the theme of recycling is as important here as it is in my prints. Do you have any practical advice that has served you well as a printmaker? My wonderful secondary school art teacher, Mr. John Alford, was very fond of using the phrase ‘The only rule is there are no rules’. Which 3 artists (past or present) would you most like to be sat with at a dinner party and why? Paul Klee – I have been obsessed with his work since I was 16, when I saw a reproduction of a painting entitled ‘A tiny tale of a tiny dwarf’ in Gombrich’s ‘The Story of Art’. When I turned the page and saw that image I remember I didn’t know whether to be affronted or delighted. How could any artist be allowed to make a painting that was so resolutely un-serious, so intricate, so densely textured, and so mysterious? I have thought about Klee and his work several time a day for the last thirty-five years. I suspect he might be rather a quiet dining companion though. So my second guest would be – William Morris – who probably wouldn’t shut up. I like his high-minded Victorian energy, his vigorous belief that art and craft could belong to - and be made by – everyone. ‘Every man an artist, and every artist a craftsman’. However, we might have to ban him from reciting his own poetry, which apparently he used to do – at length – during mealtimes. Also I would invite – Judy Chicago – who is famous for her huge 1970s project ‘The dinner party’. Like the Paul Klee painting - though on a completely different scale – this weird and wonderful work was another ‘What on earth?’ moment for me. Once seen, impossible to forget. I am fascinated by way she uses several different media – textiles, ceramics, painting, drawing, sculpture – to create large-scale projects which are uncompromising and single-minded in their ambition. Her work combines outrage, passion, technical skills, and wit. I think she would be an excellent dining companion. What projects printmaking or otherwise do you have lined up for the summer? I am presently working on a series of small lino-cut prints entitled ‘Childrens’ Games’, which are loosely based upon the activities of my 7-year old son, and memories of my own childhood. I am also trying to complete a couple of Shakespeare-themed prints (this year being the 400th anniversary of his death) for exhibition at the Globe Theatre and the Bankside Gallery. The lino for all these prints was found in a skip, so once again this is an example of recycled materials

I am finishing off a mosaic mural – commissioned by a school – on the theme of various species of birds.

I have two other large mosaic projects lined up; one of which is to build a replica of one of my earlier murals which was recently demolished.

Please visit Jim Anderson’s website www.jimpanzee.co.uk to view past projects.

And www.kenya-mosaic.com for mosaic projects

I am presently working on a series of small lino-cut prints entitled ‘Childrens’ Games’, which are loosely based upon the activities of my 7-year old son, and memories of my own childhood. I am also trying to complete a couple of Shakespeare-themed prints (this year being the 400th anniversary of his death) for exhibition at the Globe Theatre and the Bankside Gallery. The lino for all these prints was found in a skip, so once again this is an example of recycled materials

I am finishing off a mosaic mural – commissioned by a school – on the theme of various species of birds.

I have two other large mosaic projects lined up; one of which is to build a replica of one of my earlier murals which was recently demolished.

Please visit Jim Anderson’s website www.jimpanzee.co.uk to view past projects.

And www.kenya-mosaic.com for mosaic projects